Diabetes Prevention & Treatment

A Multi-Pronged Approach to Diabetes

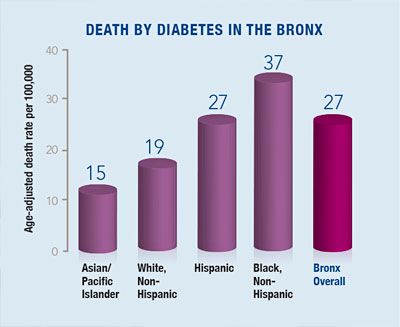

Combine obesity, poor nutrition, lack of exercise and limited access to health care and you’ve got the perfect recipe for a type 2 diabetes epidemic. Those ingredients are all too plentiful in the Bronx, where the diabetes incidence exceeds all other boroughs and ranks among the highest in the nation.

Jill Crandall, M.D.“For the Bronx and other communities across the country, the need for better diabetes treatments has never been more urgent,” says Jill Crandall, M.D., professor of medicine (endocrinology) and director of the Einstein-Montefiore Diabetes Clinical Trials Unit and the Translational Research Core of the Einstein-Mount Sinai Diabetes Research Center. Such treatments are aimed at preventing patients’ blood glucose levels from reaching dangerously high levels that can cause serious complications including cardiovascular disease, kidney problems, blindness and amputations. “We’re fortunate now to have a lot more medications than we did 10 or 20 years ago,” says Dr. Crandall, “but we don’t have very good evidence about which options will be successful over the long term.”

Making the GRADE

To gather that evidence, Einstein-Montefiore and 44 other clinical centers are conducting a major study to find the most effective combination of glucose-lowering medications for type 2 diabetes. The Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes: A Comparative Effectiveness Study (GRADE) was launched in 2013, supported by a five-year, $134 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Crandall is co-directing the Einstein-Montefiore team along with Diane McKee, M.D., professor of family and social medicine and vice chair for research in the department of family and social medicine at Einstein and Montefiore.

GRADE has randomly assigned more than 5,000 patients recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (nearly 200 of them Einstein-Montefiore patients) to take one of four glucose-lowering medications together with metformin—the most commonly prescribed anti-diabetic drug worldwide. “Although metformin is very safe and effective,” notes Dr. Crandall, “most patients eventually need two or more medications to control their diabetes. Knowing which additional therapies offer promise and which variables affect their efficacy will allow us to take a much more targeted approach with our patients.”

Diane McKee, M.D.The patients enrolled in GRADE will be followed for up to seven years. The study is tracking their blood-glucose levels and collecting data on weight, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, gut bacteria, diabetes complications, medication side effects and more, providing an encyclopedic record of how patients respond to the drugs as well as clues about the mechanisms underlying their responses.

The researchers are also carrying out ancillary GRADE studies. Dr. McKee, for example, helped guide GRADE’s recruiting procedures and recently completed a study looking at why patients decided to participate—or not—in GRADE. “We knew it was important not to just ask people why they said ‘yes,’ because that’s only half the story,” Dr. McKee explains, noting that in Einstein-Montefiore’s mostly-minority patient cohort, the “no’s” often reflected mistrust of the medical establishment and concerns that the research might actually harm them.

“People remembered the legacy of the Tuskegee experiments,” says Dr. McKee, referring to the notorious study in which black men infected with syphilis were left untreated. “To them, this wasn’t something that happened 50 years ago and just went away.” Those who said ‘yes,’ by contrast, cited factors such as the hospital’s reputation in the community, the respect with which they were approached, and (for Hispanic respondents) recruiters’ ability to speak Spanish. These insights could help improve minority-group participation in future diabetes studies.

In another GRADE-related study, Jeffrey Gonzalez, Ph.D., associate professor of medicine and of epidemiology & population health at Einstein, is investigating how different medication regimens affect, and are affected by, the emotional burdens of living with diabetes. “We’ll be looking at distress and depression as a predictor of outcomes in GRADE,” Dr. Gonzalez explains, “as well as distress and depression symptoms as outcomes of the treatments themselves.”

Testing New Therapies

Einstein researchers are also testing potential new diabetes drugs. Dr. Crandall, for example, recently completed a study of resveratrol, the red-wine compound widely used in dietary supplements for a range of supposed health benefits. Some animal studies have suggested that resveratrol could improve glucose metabolism. Dr. Crandall and her team conducted a pilot study to see if resveratrol supplements had any effect on 10 older adults with prediabetes, characterized by blood glucose levels higher than normal but not high enough for a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

Jeffrey Gonzalez, Ph.D.Resveratrol improved the subjects’ insulin sensitivity and their post-meal glucose tolerance—the first study to link resveratrol to a benefit in humans. But a larger, controlled resveratrol trial involving 30 older adults with prediabetes failed to duplicate those benefits. “Nonetheless, we did find some things that were of potential interest,” says Dr. Crandall, “including the observation that resveratrol improved a measure of blood-vessel function.”

Dr. Crandall is also Einstein’s principal investigator for a major clinical trial involving type 1 diabetes, which affects up to 10 percent of people with diabetes. Anyone with type 1 or type 2 diabetes faces an increased risk for developing kidney disease—one of the most important of all diabetic health complications. In fact, diabetes is the leading cause of kidney disease. The multicenter Preventing Early Renal Loss in Diabetes (PERL) study is testing whether the drug allopurinol can prevent loss of kidney function in people with type 1 diabetes.

Allopurinol has been prescribed for many years to decrease high blood levels of uric acid, which can form crystals in the joints that result in the painful condition known as gout. Recent evidence suggests that elevated uric acid blood levels also do something else: They strongly increase the risk for chronic kidney disease and loss of kidney function among people with diabetes. So allopurinol, which lowers blood uric acid levels, seemed like a promising candidate for protecting against kidney disease in type 1 diabetes patients. “If this medication proves useful in patients with type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Crandall notes, “it’s reasonable to expect it would help prevent kidney disease among type 2 diabetes patients as well.” The PERL study is sponsored by the NIH and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

The Lifestyle Connection

Medication is just one approach to helping people with diabetes. Diet and exercise are also crucial, as shown by the landmark NIH-supported Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), which was conducted during the 1990s at Einstein and 26 other medical centers nationwide.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 86 million Americans age 20 and older—more than one in three adults—have pre-diabetes, a condition that puts them at high risk for developing diabetes. The DPP compared different strategies for delaying or preventing pre-diabetes from turning into full-blown type 2 diabetes.

Three thousand patients with prediabetes were divided into three groups: the first received the drug metformin; the second received intensive lifestyle intervention, involving one-to-one coaching in exercise and weight loss; and the third group received a placebo. The findings, published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2002, were so compelling that the trial was halted early. People with pre-diabetes who took metformin reduced their risk for developing diabetes by 31 percent, while those who made lifestyle changes did even better: They saw a whopping 58 percent reduction in their risk for developing diabetes.

Could the people enrolled in the DPP sustain those benefits? To find out, a multicenter follow-up study called Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS) was launched in 2002 and is continuing. Dr. Crandall, who is Einstein’s principal investigator for DPPOS, says the results so far are promising.

Compared to the placebo group, people with prediabetes in the lifestyle intervention and metformin groups remain less likely to develop diabetes (34 percent less likely in the lifestyle group and 18 percent less likely in the metformin group). “These interventions clearly do have a long-term benefit,” says Dr. Crandall, noting that metformin may have other health benefits beyond controlling blood-glucose levels. For that reason, DPPOS is now monitoring metformin’s effects on the incidence of cancer, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease among its participants. Final DPPOS results are expected in about three years.

Sticking to a Healthy Plan

No matter how well a treatment does in clinical trials, it can only work if people use it. “It’s all about behavior,” says Elizabeth A. Walker, Ph.D., R.N., professor of medicine and of epidemiology & population health, and co-director of the New York Regional Center for Diabetes Translation Research.

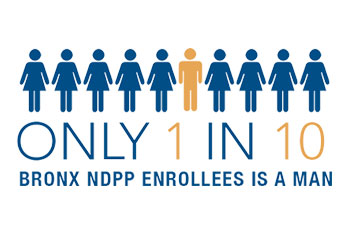

Dr. Walker wants to extend the knowledge gained from the DPP to at-risk people in underserved communities. To that end, she develops culturally sensitive interventions to help people make and sustain lifestyle changes and other self-management behaviors such as adhering to medication regimens. In one recent pilot study, Dr. Walker and her team tailored the standard curriculum used by DPP participants to better serve low-income men of color who are at risk for type 2 diabetes.

After consulting an advisory panel from the local community, the researchers learned that some of the DPP’s advice—bringing along chopped-up vegetables to a party to avoid eating unhealthy food served there, for example—failed to resonate. “The men said, ‘We’re not walking into a party with our little container of celery and carrots,’” Dr. Walker recalls. So now, the revised curriculum suggests bringing a prepackaged healthy snack, along with advice on how to read nutritional labels. The study aims to see if adapting the curriculum specifically for men improves their health behaviors and outcomes. Results are expected soon.

An effort is also underway to reduce the distress among type 2 diabetes patients that usually goes untreated and often impairs patients’ ability to control their blood sugar. Dr. Gonzalez, along with Dr. Walker and collaborators at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, is studying a telephone-based intervention aimed at reducing type 2 diabetes patients’ emotional distress and helping them stick with treatment regimens and self-care efforts. In addition to receiving coaching in diabetes care over the phone, patients may also receive cognitive behavioral therapy for training in distress-management skills if they report significant emotional distress. “This program is less costly than in-person interventions and could be an effective way to help a hard-to-reach population,” says Dr. Gonzalez.

Into the Future

Elizabeth Walker, Ph.D., and Judith Wylie-Rosett, Ph.D.Last December, Einstein investigators received a five-year, $2.9 million NIH grant to launch the New York Regional Center for Diabetes Translation Research. Directed by Dr. Walker and Judith Wylie-Rosett, Ed.D., the center also includes faculty from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai and the New York Academy of Medicine. It conducts research to improve strategies for diabetes prevention, care and self-management education, particularly among underserved populations.

“Our goal is to improve the health of people who have diabetes or are at risk for developing it, particularly among groups that are disproportionately affected by the disease,” says Dr. Wylie-Rosett, professor and division head of health promotion and nutrition research in the department of epidemiology & population health and the Atran Foundation Chair in Social Medicine. “Einstein and Montefiore have a longstanding commitment to social justice, and this center provides a way for us to share our research expertise with others trying to reduce health disparities and promote health equity.”

Posted on: Friday, September 15, 2017

Tablet Blog